1 Listen Local

Listen Local is an open collaboration for artists, fans, managers, developers to provide alternatives to connect local audiences with local artists through locally relevant music recommendations and findings. As a project of the Digital Music Observatory it aims to make big data work for small labels and self-released artists, and to make algorithms work for and not against them.

Our first demo project with the Slovak music industry, supported by the Slovak Arts Council, was heavily influenced by Cathy O’Neil: Weapons of math destruction: how big data increases inequality and threatens democracy, a book that started similar dialogues in both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, and Data Feminism by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, which applies a critical approach to data ethics informed by the ideas of intersectional feminism, and can be easily adopted to a small enterprise, small country, or ethnic bias scenario3. These very popular and critical books show how earlier inequalities in the treatment of vulnerable groups (women or racial/ethnic minorities) can be enhanced by data-driven and AI applications.

1.1 Listen Local Goals

Listen Local is a highly automated system that uses open-source algorithms for automation and open, trustworthy AI. We deploy these technologies to help humans to work with music, enjoy music and participate in music. Keeping in mind a basic principle of ethical, trustworthy AI, our system is always maintaining human agency and oversight.

In the European Union, EU High Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence defined artificial intelligence for policy purposes and laid out its suggested ethical guidelines4. It has also defined “high-risk” applications of AI that will be regulated on EU-level by the Proposal of the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act). The Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Union created a very intelligent document on the challenges of putting the regulation into practice to protect fundamental rights. This document is perhaps the first hands-on guide on how to actually implement AI regulations by regulators and courts5.

The EU’s concept if ethically applied and regulated AI is trustworhty AI. Because AI applications train algorithms from data, a complementing concept is trustworhty data. If an AI system learns from bad data, its actions will be accentric and potentially harmful. The Data Governance Act was published less than a month ago, and it has both sector agnostic and sector-specific rules. Another important measure, the Open Data Directive, is transposed into various Lithuanian laws6.

The European Union, unlike the United States, chose to create general, and not sector-specific AI regulation. Because cultural policy is regulated on national level, and because the EU High Level Expert Group made the questionable definition of high-risk AI with the exclusion of copyrights (although they are important and EU-treaty protected personal rights), currently there is no comprehensive EU policy on AI in the cultural and creative sectors and industries, where the Music Tech and the broader Art Tech scene belongs.

The problem with the current EU regulatory approach is that although it generally protects womxn, for example, because discrimination based on sex or gender is a violation of the EU’s fundamental rights, it does not give any guidance how womxn artists can be protected if music recommender systems give a smaller audience to their works than those of the male artists, and therefore they receive less royalties. Any such measures are left in the EU to voluntary ethical self-regulation or potentially for the member states’ own cultural policies. Only a few member states, including the UK, where our project is an industry partner of the Trustworthy Autonomous Systems program, have started to assess the potential adverse impacts of AI on a wider set of rules in cultural and human domains. The Dutch AI Coalition, a public-private partnership of the Dutch government institutions, public bodies and enterprises, where Reprex is a member of the Culture and Media Working Group, have started to formulate policies in the field.

Big data creates inequalities. Only very strong global corporations, leading universities and powerful governments can organize and finance systematic, large, high-quality data collections. This leaves small states and their citizens, where there are no global corporations, globally leading, well-endowed universities present with less power to collect data and train algorithms. Lithuanian music is mainly sold on the U.S.-based and regulated global platforms of YouTube (Alphabet/Google), Apple or Spotify. Their AI systems are trained on various global data resources and on their own, mainly American/Western European audiences. Currently there are no means to check if they treat Lithuanian artists similarly to U.S.-based artists supported by the global databases of major artists. We cannot be sure either if they treat women artists, or non-binary artists similarly to male artists.

The EU data policies, and EU innovation and science policies try to balance these inequalities with promoting data interoperability. Data interoperability means that various data assets can be assembled, integrated into larger data assets, like databases or datasets, that can be used, among other things, to better train algorithms with machine learning and deep learning, or to better test the potentially harmful biases of existing commercial system. A critically important, interrelated concept is metadata, information about how data should be used.

The Open Data Directive aims to foster the re-use of data that the private sector cannot collect (i.e. taxpayer funded data) for any uses in an interoperable way. The Data Governance Acts tries to encourage data altruism, where people voluntarily share their data for ethical purposes. It is critically important for our application to get open data and voluntary data sharing right. This is exactly that we are trying to figure out with the Listen Local Lithuania project.

1.2 Listen Local Milestones

- 2014: First Listen Local project to promote more local content with in-store and HORECA public preformance licensing.

- 2019: The Slovak Music Industry Report specifies the need for new instruments that help the diveristy of music recommendation and discovery in digital streaming.

- 2020: The principles of the Listen Local system were outlined in the Feasibility Study On Promoting Slovak Music In Slovakia & Abroad. This study was supported by the Slovak Arts Council and the state51 music group, and it is avaialble in both English and Slovak languages7.

- 2021: Daniel Antal (Reprex) in the JUMP Music Market Accelerator with the automated data observatory concept.

- 2022: UK TAS research grant into trustworthy autonomous recommendation systems.

- 06.03. MusicAIRE grant for Listen Local Lithuania managed by MXF.

- 07.01. Listen Local Lithuania project starts together with Listen Local Ukraine. We are start preparations for Listen Local Czechia and Listen Local Flanders.

1.3 Application Ideas

The following microservices are designed for the functionality of Ghost and Patreon. Mark, please check if it is feasibly to offer this simply on https://contribee.com/.

Criteria to consider: - Independently own, non-profit - Data ownership: if people sign up to our products, the mailing list remains with us, can we export it - Cost of collection and subscription (Patreon has no fixed fee, but takes a large % from the reveneus) - Templating options for visuals - Ease to include several tiers of paid products, see below. Subtrack is not a good solution, because it offers a simple product, we may want to offer many products for each curators and centrally as Listen Local

Ideally, some services should be offered centrally – where machine creation is crucial – and other by the curators themselves. This means that if curators put more time into curating music and have a larger following, they get more money. However, we must make sure that if a curators stops his/her affiliation with us, he or she will not use the Listen Local brand anymore. So maybe all subscriptions will have to go one account, and the money be distributed later to the curators.

1.3.1 For music curators and users

Our Listen Local App (Slovakia) was a conceptual application that changed the personalized recommendations of Spotify fulfilling various “Slovak” quotas. The user could choose, for example, to be recommended at least 20% music made in Slovakia with 10% with Slovak lyrics. Slovakia was one of the last countries to introduce local content regulation on radio (i.e. a national content quota.) The quota was not well defined, and it is difficult to fulfil and monitor it. Radio editors complained that they do not find enough suitable “Slovak” content into their playlists. Our demo showed two important insights: a) “Slovakness” is a very fuzzy concept b) we can find good content for almost any definition or aspect of “Slovakness”.

Figure 1.1: Our first demo application altered the personalized recommendations of Spotify

Ideas on monetizing: Increasing the market share of Slovak artists in radios or in personalized recommendations gives a monetary benefit for artists and producers defined as “Slovak”. It may help radio stations avoid fines.

1.3.2 Trade associations and regulators

Almost all European countries (and in fact, most of the countries of the world) use some form of content regulation to make sure that local artists remain visible and audible in local radios. A similar policy measure was introduced to film streaming – Netflix in Europe is full of European content. However, no similar measure is present in music streaming. Because music streaming is hyper-personal, regulators, policy makers and trade associations do not even have a clear view on the market share of “local” content in streaming services. What is the market share of Slovak music in Slovakia on Spotify? What is the market share of artists from Gent in Gent?

Listen Local Slovakia was a proof of concept to measure such market shares in Slovakia. The Horizon Europe consortium OpenMusE hopes to get funding from the European Commission to research and develop reliable market monitoring in a select countries/region.

Listen Local is not a market monitoring service, however, it may be an important ingredient of a market monitoring system. Current radio monitors or streaming information services are not able to tell the market share of Lithuanian music or Gent artists in a particular setting, because they do not know how to connect (the fingerprint) of music to a location.

1.3.3 For artists and managers

Listen Local is based on knowledge that goes beyond the metadata required to sell music. We place a big emphasis on location and locality, physical or imagined. Danny Vera may be the best known artist from Middelburg, Zeeland, Holland, but his americana belongs equally to Nashville, Tennessee—but not to all locations of the world.

In Listen Local Slovakia we were piloting an application that avoids an artist ending up on Forgetify… an application that only plays songs in the Spotify catalogue that nobody listened to recently, not even their friends, family, brothers and sisters, daughters and sons. ► blogpost. This could be part of service when we monitor and correct metadata problems that prevent the algorithms of Spotify or YouTube to recommend an artists music to the proper audience.

Another application could give a map of towns where the artists music may fit into the music listened to the city or neighborhood of a city. We can provide music use information on neighborhood/wijk level in bigger Western Cities, and city level on most countries.

Together with the Digital Music Observatory, we can provide individualized career advice to artists. For example, for SoundCzech we analyzed the output requirements per artist to be come a full-time artist in Austria and Czechia.

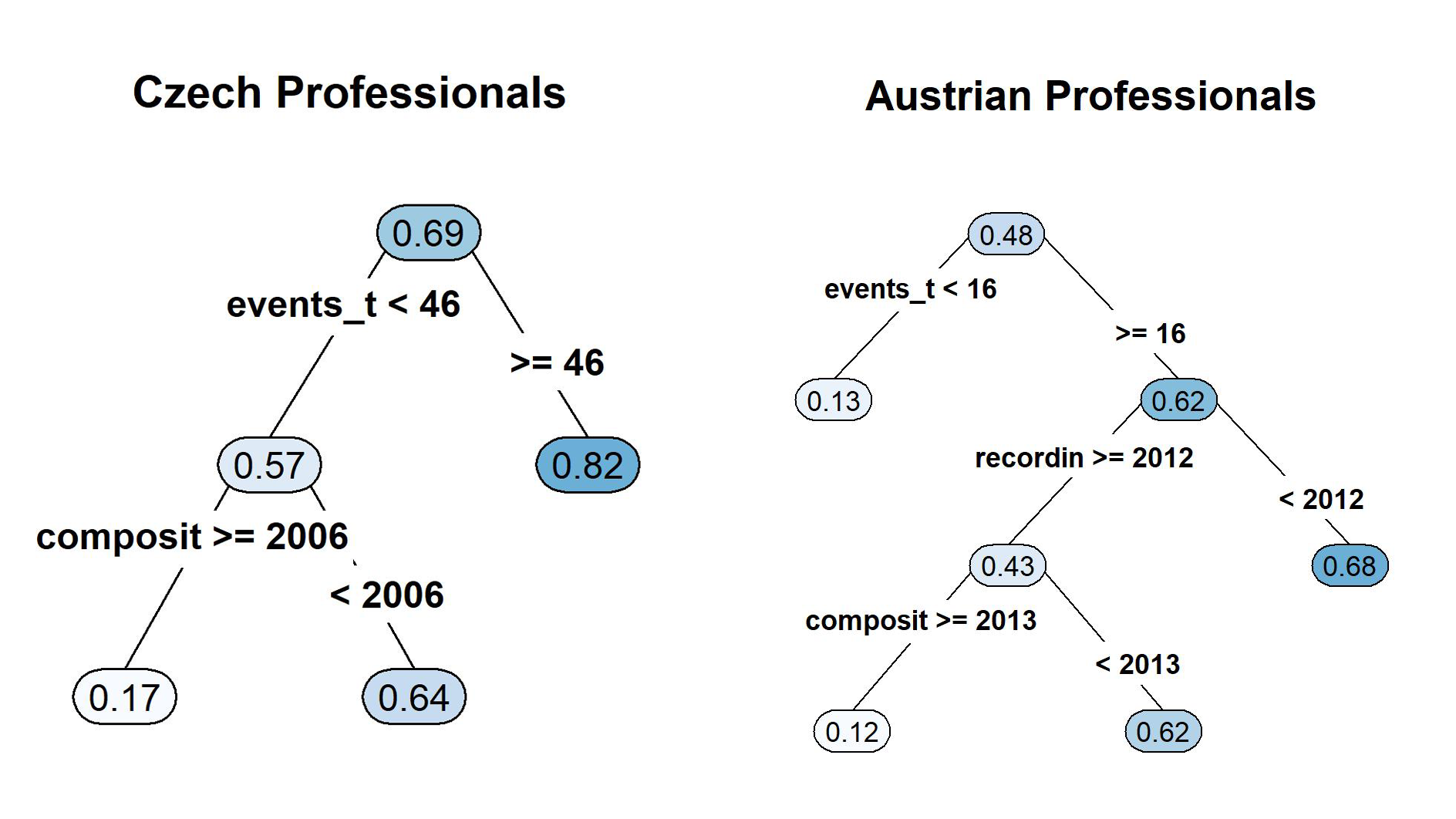

Figure 1.2: We analyzed the output requirements per artist to be come a full-time artist in Austria and Czechia for the SoundCzech national music agency.

1.3.4 First microservice prototypes for artists and managers

Get a map of cities where your music best fits in (for targetting local radio, venues, festivals)—-the artist/manager will get a PDF document with charts, maps about why her music is best suited to be played in Antwerpen, Gent, etc… f.e. 10 euros, money goes to LL, because this is machine generated.

Get a list of curated target playlists: get a list of human curated playlists on Spotify where the artist can pitch her music with a high degree of success. f.e. 10 euros, money goes to LL, this is machine generated.

Fix your musician/band biography presence – the artist will get a recommended text to include on MusicBrainz and Wikipedia, with correct references to VIAF, IFNI, Spotify, YouTube, social media channels, well formatted text and biographical entries etc. f.e. 35 euros, this may need human oversight - money is split between LL and curators or copy editor who helps in the report.

Provide all fixes for the artist: get all possible reports in one go for 100 euros (maybe a bulk service to music export offices, or foundations that support artists.), the money is distributed to contributors.

1.3.5 First microservice prototypes for venues and programmers

Recommend artist to my festival lineup or radio playlist who come from a city, country, who are womxn, queer, etc.

Machine generated version – 10 euros, money goes to LL,

Curated version, machine generated version reviewed by our local curator – 50 euros, 10 euros remain with LL, 40 euros goes to curator.

1.3.6 For Fans

Our idea with the Moon Moon Moon collective (and band) is the creation of various open-source games that use Listen Local. (Just check out a poetic letter of compaing to Buma/Stemra about their royalties…)

An unvalidated idea is the creation of a ‘music tinder’ matching smartphone application. A visitor arrives on the train to Utrecht Centraal, and our application offers images and sounds of music from Utrecht. If they swipe left, a new local artist is recommended. If they swipe right, the song is added to a user playlist (on Spotify for example) and information is displayed if there is any live performance available in town or in the user’s hometown. The matching algorithm can give a priority to bands that have a live performance for the day, the day after, etc.

Another version of this application could help music educators to discover the geography of popular and classical music. Children may be encouraged to discover the music of their home town, region, and new countries. 8

Figure 1.3: The birthsplaces of the 100 most streamed artists in the world

We hope that next year we will be crating interactive apps, hopefully even mobile apps, but in the early stage, we can only provide blogposts, playlists, reports, and possibly podcasts.

1.3.8 For fans and supports

- Subscribe to the a (curators’) playlists: money goes to affiliated curator

Listen Local Budapest will create playlists like Made in Budapest, Future Sound of Budapest, Female songwriters in Budapest, Acoustic Budapest, etc.

The playlists will be embedded in paid blogposts with a short description of the list, the curator’s personal story of the list, and a link where the user can import the playlist first on Spotify, later on other services like YouTube, etc.

Example: _We will create some playlists for free, and for the rest, they will be available for a monthly subscription fee of 1 euro. Subscribe to all lists (also a form of support) for 10 euros per months programmers, radio curators, etc can have an overview of all our lists.

1.4 Online assets

Temporary website: listen-local.net. The website, like all Digital Music Observatory and dataobservatory.eu sites are created with hugo, which is a static site generator in the Go language. The Go language is an open-source language of Google, and it is designed to build web applications that work with each other. This will come handy when we want to create paid content that is automatically generated, and/or synchronzied with a paid content site like Ghost or Patron.

We use an open-source template (family) developed by the wowchemy collective. This may not be the best for Listen Local, but I would like to start from this because I know it very well, and it offers full compatibility with all our machine-generated content. Later we can move to a different hugo template, or even have somebody design one. The good thing about Hugo templates is that they are fully interoperable.

The wowchemy templates are semi-localized to many languages, and the listen-local is currently bilingual (EN, SK). It is possible to have a separate EN, SK, LT, NL, HU blog feed where optionally the not localized content is always present in English, or only the LT blog posts are present, or there is a template in Lithuanian that shows blogposts which are only available in other languages with a very short, tweet-length summary.

Our current website(s) are modification of the Academic template. The template can create really nice, not too academic and boring sites as well, as it has a lot of dynamic components.

There are a few limitation for this particular template. If you take a look at the Digital Music Observatory contributors (persons and organizations) it puts the profile pictures and logos into a circular mask. While our logo can be square, this is how it will be displayed. I think that this is more of a plus – we will need a family of logos and a simple, uniform ciruclar look can be very pleasing to the eye.

The current color palette of the Digital Music Observatory: #007CBB, #4EC0E4, #00843A, #3EA135, #DB001C, #5C2320, #4E115A, #00348A, #BAC615, #FAE000, #E88500, #E4007F We can design a new palette for the Listen Local family if you insist, but it woudl be good to have a color palette of at least 12 very distinct colors + white, black, greys to use.

1.4.2 Online forms

We will use online forms to collect crowdsourced tips and to sign up artists. These forms will be midly customized (logo, color, but not in too much details.) One reason to for an automated social media presence on Twitter, Instagram, etc. would be to constantly ask for local recommendations.

References

In the reference: Weapons of math destruction: (O’Neil 2018), Data feminism: (D’Ignazio and Klein 2020); the first 3 chapters are particularly suitable for a general policy audience.↩︎

The High Level Expert Group’s definition of AI: (AI HLEG 2019a), proposed ethical guidelines (AI HLEG 2019b).↩︎

AI Act Proposal:(European Commission 2021), FRA report: (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 2020)↩︎

The Open Data Directive (EUR-Lex Legal Acts 2019) is a successor of the former Re-use of Public Sector Information Directive, which had been transposed into Lithuanian law since EU accession. The new measures were transposed in 2021: (Teisės akto tekstas 2021). The Data Governance Act is directly applicable EU law (EUR-Lex Legal Acts 2022)↩︎

Slovak version: (Antal 2020b), English version: (Antal 2020a).↩︎

Source: Dataisbeautiful↩︎

1.4.1 Social media

Twitter handle: @listen-locals We should have a corporate Spotify account, the Spotify account profile logo is also circular. However, I think it would be cool to have a square logo-ish family for each playlist.

The listenlocal handle is taken, national versions are possible, and we use heropost to automate tweets, LinkedIn, Instagram etc posts. It can be very handy, if we have enough content, on Twitter it can quickly build up a large presence.

For example, we have a LL LT and LL HU logo, and then the playlists are something

Listen Local HUFuture sound of BudapestListen Local LTAcousting VilniusI am sure that after a while we want a YouTube Channel, and possibly playlists on Deezer, Apple, etc.

There is an interesting and famous Dutch concept design, the Koolhas EU flag concept that was not accepted. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Union-europea_segun_rem-koolhaas.svg

It is a barcode made of the EU flags at the time. I could imagine something along these lines for the national version of the LL Logo, and in that case we have to make sure that the flags still use a kind of comprehensive palette for the national colors. You can also use the dial numbers, it is geeky, to be honest, I less and less know dial numbers as people will dial less and less. The airport codes are relevant for our borderless music travel idea, but they are not applicable for small towns. However, we can use AMS, BUD, for large cities, and for small towns make 4-letter version which would also show the small locality aspect, GENT, ESZT (Esztergom) SZGD for Szeged, as long as they do not get a secondary meaning.

We have the currently dormant Data & Lyrics Blog that can be a general purpose blog for the Digital Music Observatory, Listen Local and any related ideas. Since it is a hugo blog, any relevant post can be taken to Listen Local website, too.